Cord Cutting and the Cable Cabal

This is the second in a series of posts discussing Free Press’ new report, “Combating the Cable Cabal: How to Fix America’s Broken Video Market.”

Rapidly rising cable fees are sending some subscribers looking for a pair of metaphorical scissors so they can cut the cord. In 2009, pay-TV adoption reached an all-time high at 88 percent of American households. But it started a slow decline thereafter, reaching 85 percent at the end of 2012.

While estimates vary, it appears that some of this decline is due to cord cutting, with at least 5–6 percent of U.S. households relying exclusively on a mix of free antenna-delivered broadcast TV and online sources for their video entertainment.

Cord cutting certainly has its appeal. It’s substantially cheaper than traditional cable. All the popular (and unpopular) broadcast content is available for free and in high definition with the use of a cheap antenna. Plenty of cable content is available for free online. And there’s always Netflix, Hulu Plus, Amazon Prime, YouTube, Vdio, Vimeo, iTunes and others to fill in the gaps.

These online options offer consumers substantial cost-savings — and an alternative to the increasingly stale linear-channel model. For some viewers, the idea of sitting down at exactly 9 p.m. on a Thursday to watch 20 minutes of their favorite sitcom interspersed with 10 minutes of ads is passé.

Cable distributors have long downplayed the threat cord cutting poses to their businesses — even as they do everything they can to stifle online video competition. Cable companies have a history of blocking Internet applications used to distribute video. Cable providers also discourage cord cutting through the use of data caps and high overage fees, restrictions the industry admits have nothing to do with managing network congestion (because there isn’t any congestion to manage).

Comcast has taken this discrimination one step further, turning off the data meter when its customers stream Comcast’s Internet video content — but leaving it on for its competitors’ offerings. Charter, the nation’s fourth-largest cable company, even refused to air a commercial from an over-the-air antenna company because the ad dared to point out that cable companies could “lose a ton of money when people realize they don’t have to pay [them] to watch TV.”

Aren’t cable companies great? They force their broadband customers to help pay for the rapidly rising fees the cable-channel owners demand … and actively thwart their broadband customers’ quest to find a better way to get their video entertainment.

So your local cable company is a big reason why America’s video market is broken, and why it’s not going to get better any time soon.

But while cable distributors were once the main villains in this story, their partners in crime — the cable-channel owners — are increasingly driving the soaring prices in our cable bills.

As impressive as the cable distributors’ fiscal performance was through the recent economic downturn, it pales next to the growth the cable-channel owners enjoyed. From 2007–2011, total cable-programmer revenues grew by 36 percent, a result analyst firm SNL Kagan characterized as “pretty impressive given the brutal recession that we were in during this period.”

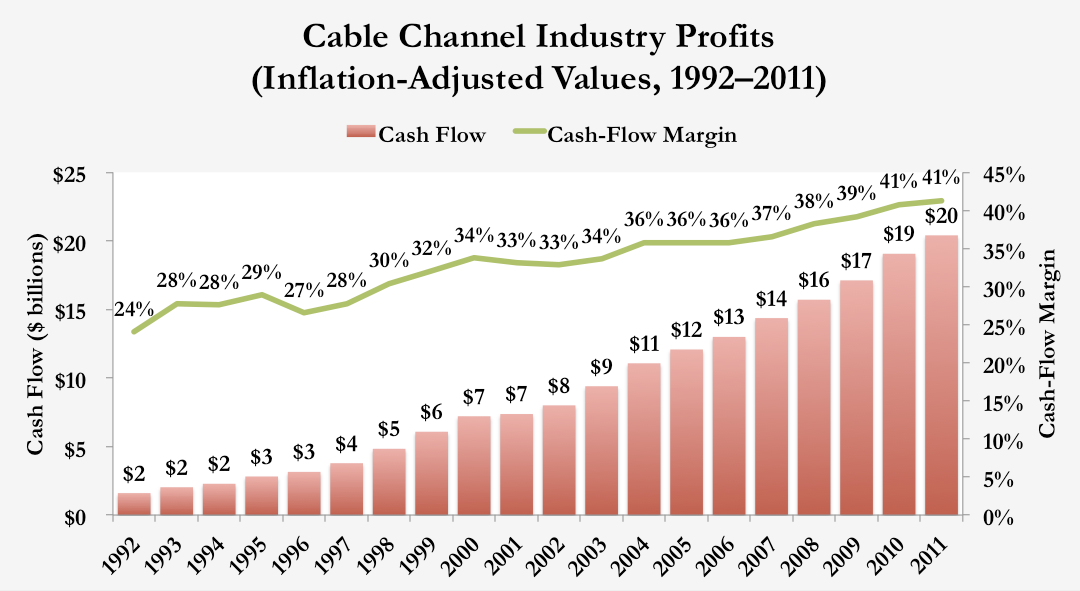

Over the past two decades, the programming industry’s collective operating profit margin rose from 24 percent to 41 percent (a noteworthy result considering the average operating margin for all S&P 500 companies over the past five years was only 14 percent). During this period, the industry’s profits increased 10-fold in real value, to $20 billion at the end of 2011.

Sources: SNL Kagan, Free Press Research

It’s true that the cable programmers’ cost of doing business has increased dramatically over the past two decades. The owners of sports channels are forking over record amounts of cash to secure broadcasting rights from monopoly sports leagues, and basic cable channels like AMC and FX now produce high-quality original programming in addition to running their usual syndicated fare.

But while the programmers’ own costs are rising, they are more than making up for it by charging the cable companies substantially higher fees for the rights to carry their channels. From 1992–2000, the programmers increased the licensing fees they charge distributors at the same rate their own expenses grew.

But since the turn of the century, the programmers have exercised their pricing power and raised licensing fees at rates outpacing their own cost increases. From 2000–2011, the cable programmers’ own expenses increased by $15 billion, but their revenues rose by $33 billion, with 60 percent of this increase coming from the licensing fees ultimately paid for by cable subscribers.

These fee increases are continuing even as many broadcast and cable networks are losing viewers. Over the past decade, nine of the 25 most-watched cable networks experienced a decline in primetime viewership, yet all raised their per-subscriber licensing fees. Six of these nine channels enjoyed higher profit margins despite losing audience share.

In our next post, we’ll take a closer look at the industry’s practice of forced bundling and examine which channels are driving cable-bill inflation (spoiler: it’s the sports channels). We’ll also examine how consumers are changing their viewing habits in response to these higher prices.