We Fight Today for a Better Tomorrow

Monday marks the official commemoration of what would have been Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s 85th birthday. For many around this country (and the world) it will be a day of remembrance, reflection and service to others.

For my 6-year-old daughter, it is a day off school.

Like many kids her age, she asks a lot of questions. She wanted to know why it was a holiday, so I explained to her who Dr. King was, and why we as a nation honor his legacy. I did this at a level that a 6-year-old can understand: When Dr. King was alive the world was a different place. People were really mean to other people just because of the color of their skin. Because of Dr. King’s work, you get to go to school with all of your friends and not just the ones that look like you.

She kind of understood this, but kids that age are so innocent that I don’t think she really got it, and that’s a good thing. So I pulled up video of Dr. King’s “I Have a Dream” speech on YouTube, so she could see and hear him speak (and I was glad that the open Internet enabled this, even though I’m not sure what the copyright issues are).

It’s a speech we’ve all heard many times, but one that is seemingly more powerful each time you hear it. Watching it with my kid, I was drawn in by Dr. King’s emphasis on the future he desired for his kids.

“I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.”

This is probably one of the most memorable lines of this speech full of memorable lines, because to those with children, wanting a better world for them is the backdrop to everything you do. This is an example of why Dr. King was such a gifted orator and one of the most effective agents for social change in American history: He had a unique skill in using his words to make people look inward before they acted outward.

The Communications Tools for Change

So naturally, as I listened to Dr. King’s words for the umpteenth time in my life, I thought about the open Internet work that has consumed all of my waking (and sleeping) time these past few days, ever since the D.C. Circuit court handed down its ruling tossing out the FCC’s Open Internet rules.

And I thought about it not in terms of what I’m working for today, but what the world will be like when my two daughters are grown.

As I listened and watched the massive crowd hang on every one of his words, I thought about the unseen blood, sweat and tears that went into organizing for that moment.

Social justice activists today have social media, blogs, email, video chats and other organizing tools to rally support, and these tools are all there because of the open Internet. Watching the footage of the massive crowd gathered for the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, I imagined that given the relatively short period of time that Bayard Rustin had to manage the logistics of this unprecedented event he probably spent a lot of time using the phone.

I recalled how instrumental “WATS” phone services (predecessor to 1-800 long distance lines) were to the Freedom Movement organizers as they evaded attempts by local law enforcement and the Ku Klux Klan to shut them down or kill them.

I thought about how the speech prompted the FBI to further target the Southern Christian Leadership Conference — and Dr. King — as an “enemy of the United States.”

And I wondered: If the phone network was not a common-carriage platform, required to be open and nondiscriminatory to all, would Rustin, A. Phillip Randolph and Dr. King have been successful mobilizing the masses for that historic event? Would the freedom movement have been destroyed completely?

I’m glad I don’t need to worry about those “what ifs,” because the network was open. And it helped create a better future.

The fight for an open Internet that we wage at Free Press is not about today — it’s about the future. Like many big public policy debates, it’s about the world we want to leave for future generations.

In a world where the owners of the network get to decide what speech flows over the network, will it be possible to organize against injustices that the broader society and powers that be find acceptable?

These Kids Today ...

D.C. communications policy debates are strange, because they tend to be somewhat focused on the past while simultaneously ignorant of the details of history, and why we made the choices we’ve made in the past.

For example, you’d be hard-pressed to find anyone arguing that we need to abandon basic common-carriage principles for phone calls. Indeed, there’s broad agreement from companies like AT&T and consumer advocates that the common-carriage principles that have and currently apply to wired and wireless voice service should continue even as the underlying technologies evolve.

But voice is just a service that uses common-carrier networks. The FCC killed common carriage for data in 2005, right as there was a major societal and generational shift from voice being the primary communications application to data being the primary way we connect to each other.

Kids today barely use voice calls. They speak to each other through data — text messages, social media, sometimes even email. The technology may have changed, but the societal and policy reasons for having common-carriage obligations haven’t.

The ability to “reach out and touch someone” of your choosing without interference from the network owner is just as important in a data-centric world as it was in the voice-centric world. The ability to connect affordably to these networks no matter where you live still matters, as does your right to keep your communications private.

I hope that FCC Chairman Tom Wheeler realizes this when he talks about the importance of the “network compact.” My kids deserve to have an open and nondiscriminatory communications platform, just as he always had, and just as I’ve always had.

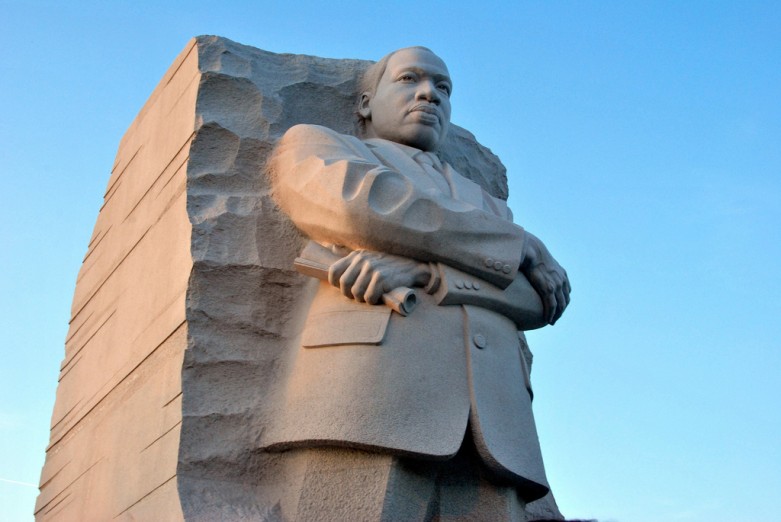

Original photo by Flickr user Angela N.