For Telco Industry Hacks, 'Progress' Is Just Another Word for Crony Capitalism

This piece originally appeared on the Huffington Post.

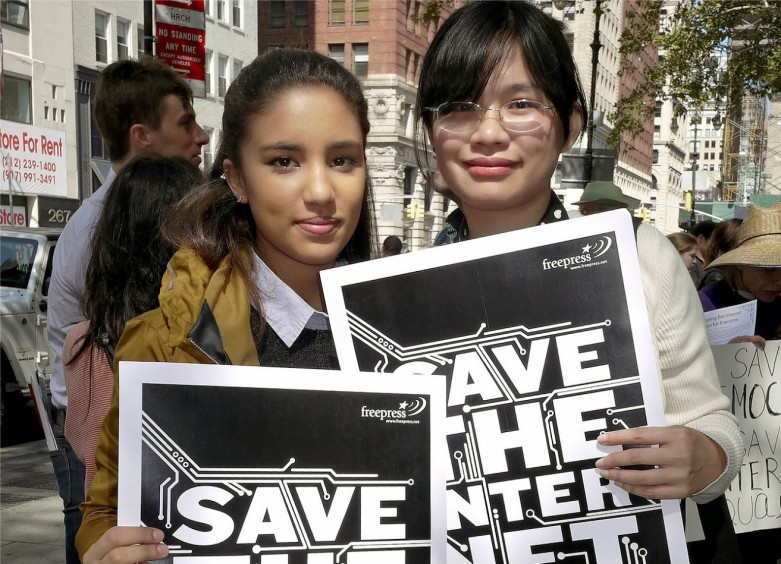

The Internet's politically engaged public is here to stay. Millions of people have begun to use online tools to engage in policy fights and protect our online rights — most recently to secure historic Net Neutrality rules at the Federal Communications Commission.

That's a good thing. But it's rattled the cages of those on the losing side of these battles. Many of their responses don't deserve to be taken seriously. But every so often something emerges from Washington that is so reckless and repugnant that it cannot be ignored away.

On April 1, the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation (ITIF), an industry-funded think tank, convened a panel of industry-funded "experts." ITIF held the D.C. event to blast what it calls "tech populism" — embodied, speakers said, by groups like Free Press, the ACLU and the Electronic Frontier Foundation. In its place panelists touted "tech progressivism" — for which industry-funded think tanks like ITIF and the Progressive Policy Institute are the supposed standard-bearers.

Tech populism threatens innovation and the economy, argued ITIF President Robert Atkinson in his opening comments. Its practitioners, Atkinson said, are "emotional" and "self-interested." Reason and the "benefits of progress," on the other hand, motivate tech progressivism — which is really just another name for the cozy alliance between the corporate sector and government that had written tech policy for decades.

Tech populism elevates the input of the Internet masses, creating online vehicles for people to engage in the political process. Tech progressivism is a closed-door, gentlemen's negotiation between businesses like Comcast, government actors that Comcast lobbies, and so-called experts like the Comcast-funded fellows at ITIF.

According to Atkinson and his colleagues, the public should trust that this insular process will lead to policies that serve all of our interests. Rather than engaging, people should just sit back and wait for the corporate-government pact to bestow its benevolent dictates upon us.

In this backwards equation, Atkinson casts newly engaged Internet users as straw men. We tech populists rely on mob rule and a distrust of authority, he claims. It's the enlightened few, tech progressives like Atkinson and his corporate cronies, who must intervene in tech policy before we do any more damage.

Progressivism in Reverse

Two fairly recent developments have compelled Atkinson to play such a pitiful hand.

In 2012, millions of Americans joined forces to successfully defeat two draconian copyright bills — PIPA and SOPA — which would have rewired the Internet to block enormous amounts of online content, including content that didn't violate existing copyright laws.

ITIF, of course, supported the movie and recording industry view that PIPA- and SOPA-style Internet filtering could be good for the people.

Another blow to Atkinson's world view came in February, when the FCC voted on behalf of Internet users to safeguard Net Neutrality under Title II of the Communications Act. Rather than simply following the industry's directives, FCC Chairman Tom Wheeler credited the 4 million Americans who took action on Net Neutrality for changing his mind. The activism compelled Wheeler to craft enforceable protections against industry efforts to block, throttle or otherwise interfere with online content.

ITIF opposes this approach and instead thinks that the public should get out of the way so ISPs like AT&T, Comcast and Verizon can serve as gatekeepers to online content. (That some of these same companies and their trade groups finance ITIF has nothing to do with the organization's positions, of course.)

For ITIF, democracy should NOT involve such public participation in policymaking. Amplifying the voices of people in the tech arena is "extremely toxic" to progress, Atkinson writes. Instead, he yearns for a return to the past, when public policy was forged behind closed doors in discussions between small groups of white people.

To illustrate this ridiculous point, Atkinson projected a slide at the April conference that depicts his ideal — six white people in a semi-circle apparently debating weighty matters:

Going back to this future "recognizes [the] vital roles of industry and government," argues Atkinson. The rest of us are too distracted by populist urges to be trusted. We'd rather steal Beyonce's latest track than give Queen Bey her due. We want to run red lights, "demonize robots" and hog bandwidth without regard for the greater good.

Broadband Dysfunction

This far-fetched interpretation of progressivism harkens back to a not-too-distant time when the companies that bankroll ITIF's existence effectively wrote their own policies.

This approach let AT&T, Comcast and Verizon award themselves with tens of billions of dollars in state and federal tax subsidies over the past decade. This corporate welfare is the result of the insider negotiations Atkinson holds dear. In this case, tax benefits and policy favors were offered to these companies in exchange for promises to build out high-speed Internet networks to underserved neighborhoods.

Verizon, which is the worst of the bunch, paid no federal income taxes between 2008 and 2012, according to studies from the Citizens for Tax Justice and the Institute for Taxation and Economic Policy.

At the time Verizon had promised policymakers that it would plow billions of dollars into connecting a vast swath of the country to fiber-to-the-home Internet services. But by 2013 the phone giant had backed away from this pledge, connecting only a fraction of those communities. And it simply pocketed the benefits that were offered in the expectation that the company would fulfill its half of the deal.

Industry-written policy has brought us higher broadband bills, limited choice among providers and efforts to stifle the creativity of entrepreneurs and the broader public. The millions of people who submitted letters to the FCC, called Congress and rallied across the country for real Net Neutrality are a grassroots rejection of this kind of top-down policymaking.

Letting companies like AT&T, Comcast and Verizon call the shots has damaged America on a global scale, too. In March, cloud-services provider Akamai released its fourth-quarter 2014 state of the Internet report. While the annual global average for Internet speeds grew by 20 percent, according to the survey, the United States' international ranking declined in all speed categories from the previous quarter, placing us behind most developed countries in Europe and Asia.

The Center for Public Integrity's new report finds that the high cost of broadband and the lack of competition is the reason broadband adoption has slowed in the United States, where approximately 25-30 percent of the adult population lacks a high-speed connection at home.

CPI compared five U.S. cities to five cities of similar size and density in France and found that "prices in the U.S. were as much as 3 1/2 times higher than those in France for similar service."

What accounts for the difference? "Consumers in France," CPI notes, "have a choice between a far greater number of providers — seven on average — than those in the U.S., where most residents can get service from no more than two companies."

Business as Usual

These are the facts that Atkinson's "facts-based" analysis ignores. Tech policy shouldn't be hashed out by government, the phone and cable lobby and its paid functionaries.

This approach has left large swaths of the country on the wrong side of the digital divide — and returned jaw-dropping profits to the handful of Monopoly-minded carriers that provide access.

Industry hacks are loathe to acknowledge the many ills plaguing U.S. Internet service. They dismiss public concerns about the country's second-class broadband status. They write intellectually dishonest white papers declaring that America's Internet is just hunky-dory — the best in the world, in fact.

Internet users are calling their bluff. That we're emerging as an outspoken political force scares groups like ITIF to death.

Rather than engage, Atkinson pines for a dysfunctional past when Internet users were muted in favor of those paid to parrot industry positions.

This is not progressivism, and it's not public service, but a feeble effort to restore business as usual in a town where phone and cable companies have dictated the rules for too long.