Net Neutrality, in a Nutshell, Is a Nondiscrimination Law

I spoke yesterday to Net Neutrality advocates and supporters who are wondering how the current legal battle over the FCC’s open-internet rules fits into the history of this issue. Here’s what I told them in what they billed as a five-minute “lightning talk” on the topic.

Whatever your background or connection to Net Neutrality, you probably heard a lot more about it last week, when even through the rush of holiday travel the issue broke through into “old” media channels, social media and Thanksgiving dinner conversations.

All of this was sparked by the news that Trump’s FCC chairman, Ajit Pai, plans to undo the Net Neutrality rules set in place in 2015 during the Obama administration.

So in this lightning-round discussion, I’ll talk about what Net Neutrality is and its legal history before launching into the important question of where we go from here.

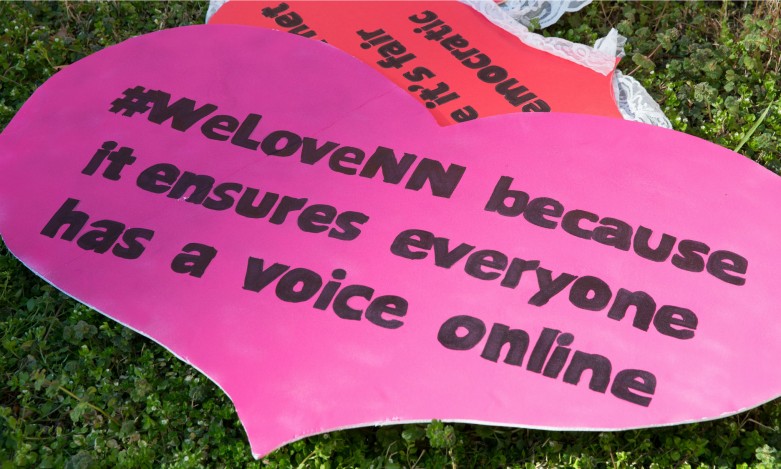

Free Press and Free Press Action Fund, with our allies, are fighting back in the courts, in Congress and in the streets. We’re seeing nationwide protests to stop Pai’s plan, and we will sue the FCC if the rules are overturned. But what exactly are we fighting for?

At risk of switching forces of nature in a lightning talk, I’ll talk about gravity instead of lightning.

My wife is a kids’ musician who sings fun songs about science. One of her lyrics says “Gravity is not just a good idea, it’s the law!”

That’s what Net Neutrality is: not a law of nature, but also not simply a good idea. This longstanding law has changed forms and evolved over time, but it’s been with us as long as we’ve had communications networks.

Our laws have always said that two-way communications networks must be nondiscriminatory. And as former FCC Chairman Tom Wheeler came to understand in 2015 after a lot of good advocacy from people like you, the communications rights the law grants do not and should not change even as the technology advances and evolves.

So that’s Net Neutrality in a nutshell. It’s a nondiscrimination law.

Just as your phone company can’t tell you who to talk to or what to say on the phone, your internet access provider can’t dictate what you say or see over your internet connection.

Legal battles have swirled around this issue for decades now over both the wisdom of FCC rules safeguarding these rights and the legal underpinning for them.

The Communications Act establishes the FCC’s mandates, and it classifies communications services in a few different categories.

Among those classifications are “information services” — things like websites, apps or other kinds of content you access online; and “telecommunications services” — the services that transmit information for you.

Let’s think of phones again for a second: Your voice is the information transmitted, and the telephone service is what transmits it. Telecom services that transmit our information are governed by Title II of the Communications Act.

Beginning in the George W. Bush administration, in a misguided attempt to more or less completely deregulate broadband, the FCC started to tinker with those classifications. It said broadband wasn’t a telecom service but was in fact so “inextricably” bound up with internet information that broadband was also an “information service”.

The Bush FCC said that broadband providers like Comcast, websites like YouTube and apps like Twitter all fit into the same category under the law.

Having reached that decision, the Bush FCC and the first FCC chairman in the Obama administration, Julius Genachowski, still tried to retain nondiscrimination (i.e., Net Neutrality) principles for internet access service.

That approach didn’t stand up in court. The FCC said it could prevent things like blocking, internet-traffic throttling, paid prioritization, and discrimination by broadband providers — but it did so without treating those companies as telecom service providers, or what the law calls “common carriers” under Title II.

Each time the FCC did that, broadband companies sued and won. In 2010, Comcast beat the FCC in federal court on the Net Neutrality principles that the Bush FCC retained, even as those Bush appointees turned away from the correct legal framework for these rules.

After restoring Net Neutrality rules without first fixing the legal framework, the FCC lost in court again — this time to Verizon, in 2014.

Then in 2015 Chairman Wheeler’s FCC finally got it right — again, thanks to tons of hard work from open-internet supporters.

The Wheeler FCC put rules into place that prevent ISPs from blocking or discriminating against online content and traffic. And it put those rules on solid legal footing by restoring the Title II legal classification for broadband.

Since then, federal appeals courts have twice upheld that FCC decision as the agency defended the rules and their legal framework with help from groups like Free Press, Open Technology Institute, Public Knowledge, the National Hispanic Media Coalition, Color Of Change, CREDO Action, Demand Progress, Fight for the Future, the Center for Media Justice, Common Cause and dozens more.

But Ajit Pai wants to undo it all. Claiming — despite evidence to the contrary — that the Net Neutrality rules and Title II laws harm innovation, investment and “freedom” for cable and phone companies, Pai and his fellow Republicans at the FCC want to flip the classification for broadband back to the wrong one.

And they want to throw out all of the Net Neutrality rules too.

Under Pai’s plan, the FCC would have no real power to prohibit bad conduct — leaving us with only empty cable- and phone-company promises to behave, and stripping away any FCC role in monitoring those promises.

Pai’s FCC also wants to preempt states’ ability to step in and fill the void it’s creating, and it’s ignored the fact that the record in this rulemaking is plagued by procedural irregularities, fake comments and missing consumer complaints.

All Pai and his fellow Republican commissioners seem to care about is their rush to make this wrongheaded decision and throw out the rules.

We’re working round the clock to stop the FCC from voting on this change at its Dec. 14 meeting, and we’re calling (and calling) on members of Congress to amplify that political pressure.

But if the agency votes the wrong way, we’ll take it to court again. We’ll challenge both its legal-classification decision, and its choice to cast aside all of the rules, as arbitrary, capricious and contrary to law.

And we won’t stop fighting to uphold the nondiscrimination rights that internet users have thanks to this longstanding legal tradition.