Broadcast, Broadband and Bundle Bloat

This is the third in a series of posts discussing the findings in Free Press’ new report, “Combating the Cable Cabal: How to Fix America’s Broken Video Market.”

What’s on tonight?

For many Americans, the answer is “nothing worth watching.” Broadcast networks, once the kings of primetime, are in the midst of a historic ratings decline. And though there are some bright spots on the cable dial, the audiences for some cable channels are also dwindling.

But while many cable channels are posting lower audience ratings, their owners are ratcheting up the fees they charge cable providers to air programming. And these providers, once willing participants in this highway robbery, now find themselves in a saturated market full of rate-increase-weary customers.

So why don’t the cable providers just tell the programmers to stick their fee increases where the sun don’t shine?

Because they can’t.

All Aboard the Bundle Bloat

Consumers aren’t the only ones who are force-fed bundles of channels they don’t want just to get the ones they are interested in. Cable providers are in the exact same position.

Consider, for example, the recent dispute between Cablevision and Viacom. Cablevision wanted to carry Viacom’s popular “must-have” channels aimed at children (Nickelodeon), young adults (MTV), African-American audiences (BET) and comedy audiences (Comedy Central). Viacom told Cablevision that to get these channels it also had to purchase and place on its entry-level tier more than a dozen unpopular channels (such as CMT Pure Country, TeenNick, and VH1 Soul).

Viacom doesn’t care that VH1 Soul’s ratings declined by 75 percent from 2010–2012. Viacom simply told Cablevision that if it wanted only the popular channels, it could have them — for one billion dollars more than the price of the entire bundle.

The cable industry calls this practice “wholesale bundling.” But antitrust law has another term for it: illegal product tying.

It’s easy to see why large programmers like Viacom are so enamored of the wholesale bundling model. Because its fees are not directly related to the size of each channel’s viewing audience, programmers can earn healthy profit margins simply by repackaging low-cost content and forcing distributors to carry these low-demand channels on their entry-level tier.

Now, the owners of many of these barely watched channels might try and make us feel better by pointing out how cheap they are. That relatively low price may offer consumers the cold comfort that certain channels don’t cost much. Hardly anyone may be watching the Hallmark Movie Channel, but at least its per-subscriber fees are just a couple of pennies a month.

But there are many channels with minuscule audiences that do demand relatively high license fees. And most of these are sports channels offering niche programming that even many sports fans have no interest in.

Root, Root, Root for the Home Team (Might as Well, Since You’re Already Paying Them)

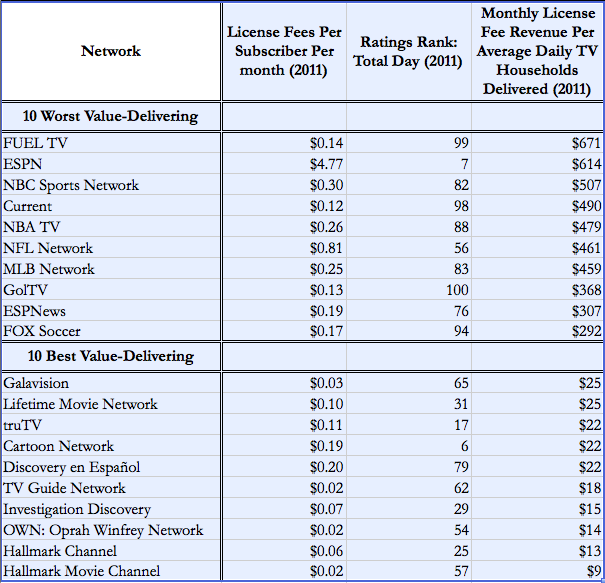

Sports networks account for nine of the 10 worst value-delivering channels. For example, News Corp.’s Fuel TV has one of the smallest audiences among rated networks yet reaps per-subscriber licensing fees that are greater than those earned by half of all rated channels.

Sources: SNL Kagan, Free Press Research. Value = total license-fee revenues divided by average daily household’s viewing.

In some markets, sports channels account for more than 50 percent of a subscriber’s monthly TV bill. And it’s only going to get worse.

Because live sports content is DVR-proof, it’s more valuable to advertisers who want viewers to actually watch their commercials. Both Disney (which owns the ESPN suite of channels) and News Corp. (which owns the FOX Sports networks) are forking over record amounts of money to secure broadcasting rights from sports leagues, and both are creating new expensive channels that consumers will be forced to buy.

Cable providers don’t like this trend any more than consumers do, but since Disney and News Corp. own a handful of “must-have” channels they can force the providers — and ultimately, consumers — to pay for everything else.

Enter the Internet — and a Shift in Viewing Habits

While rising costs from sports and wholesale bundling are threatening the coziness of the cable cabal, this trend is not likely to progress far or fast as long as vertically integrated companies like Comcast control both programming and distribution. Technological innovations represent the first glimmer of hope for consumers wanting a way out. These innovations, combined with never-ending rate increases in a weak economy, are starting to disrupt the existing video business model.

Cord cutters draw the bulk of the media attention, but the real sea change in this market lies in how all consumers are displacing traditional linear channel viewing with online and time-shifted content.

For those in the advertiser-coveted 18-to-34-year-old demographic, traditional TV watching accounted for less than 60 percent of the total time spent watching a video screen in the last half of 2012, substantially below the level seen in older age groups. Those in the narrower 18-to-24-year-old demographic spend approximately 30 percent of their daily screen time on the Internet, with more than one-tenth of their total screen time spent watching online or mobile video content. In the second half of 2012 alone, the time this age group spent watching online video (fixed and mobile) increased by 32 percent.

While this trend is strongest among youth, online video-viewing time is rising for all Americans. For the population as a whole, the time spent watching online video increased by 17 percent, from 11.2 hours each week in the middle of 2012 to 13.1 weekly hours by the end of 2012. The cable cabal’s reliance on rate hikes only adds fuel to this technology-enabled disruption’s fire.

It’s tempting to view this shift as a natural market evolution that will proceed as Adam Smith’s invisible hand intends. However, given the scores of failures in the multichannel market, the pricing power the cabal enjoys, and the fact the cable providers also control the broadband pipe, it’s clear that any consumer-driven market change will face resistance. No amount of technology can disrupt the status quo if the channel owners and cable providers try to thwart the online, over-the-top video-delivery threat to their business model.

Unless Washington gets serious about fostering truly competitive video and broadband markets, consumers looking to online video alternatives should expect an incomplete, cumbersome and ultimately unsatisfying experience.

In our final post, we’ll discuss policies needed to remedy the video market’s failures.